Insurgencies and armed groups pose a threat to development efforts in nearly every region of the world. In the face of such realities, when I started at Creative, I was tasked with revitalizing the company’s thinking around the management of armed groups and actors.

In my experience working with disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR) strategies, I’ve seen firsthand the high rate of failure of former fighters going through these programs to successfully reintegrate. Based on these results, I’ve investigated a theory of change that repositions DDR as a governance issue, rather than a livelihoods one.

Recently, I’ve dedicated my time to exploring the link between armed group and actor engagement and governance as it relates to DDR processes. Part of my research included looking at Creative’s history with DDR projects in Central America and Southern Africa, case studies of other reintegration efforts and discussing the issue with my colleagues Jeff Fischer, Senior Electoral Advisor, and Jeffrey Carlson, Electoral Education and Integrity Practice Area Director. With Fischer and Carlson, we’ve recognized that exploring the link between armed groups’ reintegration and governance—or, more pointedly, electoral processes—is critical to bringing stabilization to some of the world’s toughest situations. Made readily apparent is the link between armed group and actor reintegration and governance—specifically DDR and electoral processes, historically and in contemporary stabilization.

We recognized that Creative’s early DDR successes in places like Mozambique, Angola and Namibia were contingent upon the foundational and follow-up elections. However, what we call “political” reintegration remains among the most underserved elements of DDR programming. Relevant for both individuals and groups, political reintegration is the programming required to inform and motivate former combatants to become stakeholders in governmental elections and political processes, as well as assist armed groups transform into political entities.

Conflict and Political Reintegration

Several case studies from different parts of the world shed light on the spectrum of success and shortcomings of political reintegration projects.

Southern Africa’s experiences with armed groups in the late 1980s showed what political reintegration outcomes can look like in different contexts. “Liberation Struggles” were transformed into political parties and “Freedom Fighters” were assisted through the formation of veterans’ associations. Mozambique and Angola, for example, demonstrate how successful DDR work can be offset by regional electoral violence.

More recent cases include the Irish Republican Army (IRA) in Northern Ireland and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). The FARC has been unable to coalesce into a political party. The IRA transformed from a group engaged with armed political violence to a political entity signaled by a final ceasefire in the summer of 1997 as its political wing, Sinn Féin, re-engaged in the peace talks. This led to the 1998 Good Friday Agreement a year later and eventually to DDR processes under international supervision beginning in 2005.

These cases illustrate how DDR efforts that don’t lead former fighters into political reintegration prolong countries’ road to peace.

However, Burundi’s story shows the other side of the coin, demonstrating the viability of political reintegration in electoral processes. Burundi’s National Forces of Liberation (FNL) was required to undergo a DDR process in order to compete in national elections as a political party. The political directorate of the FNL renounced the use of arms and registered as a political party. Transforming from an armed group into a political wing eligible for elections, the FNL became a poster child case of DDR’s potential success as a political process.

These cases point to how countries’ response to the political reintegration, or lack thereof, of its armed actors can differ vastly across the spectrum. They reveal that different characteristics of the armed groups need to be clearly recognized so political reintegration projects can be designed with those traits in mind. Likewise, the kind of armed group interface with the type of election undertaken, whether it’s national, regional, local, or referenda, will have a bearing on how the political reintegration of such groups should be crafted.

With the armed group reintegration-electoral interface in mind, it is important to consider the determination of armed groups and actors to stand for elections, versus the need to disband the group while former members become eligible voters.

For example, national elections offer the opportunities of reintegrating into parliaments and offer a kind of political empowerment to participate in an organized contest. Reintegration on the sub-national electoral level, particularly on the local level, must be implemented through a strategy that does not foster incentives for the capture of local governance by former combatants to exploit its resources. And, the reintegration strategy during a referendum must consider whether the ex-combatants have a stake, one way or another, in the outcome and whether such loyalties would inhibit genuine reintegration from occurring.

Transformation and Restoration

A traditional understanding of DDR entails conducting initial efforts to reconcile former fighters and armed groups in a post conflict agreement as a political process with a programmatic response. As such, political reintegration can be both transformative and restorative.

In the transformative dimension, treating armed groups as constituents of a nations’ polity may facilitate their conversion from a non-state armed actor into a political party whose members are eligible to run for office. As a restorative measure for an individual, it implies the return to a place in society with civic rights and responsibilities, including the right to vote. Civic education campaigns are intended to inform and motivate ex-combatants.

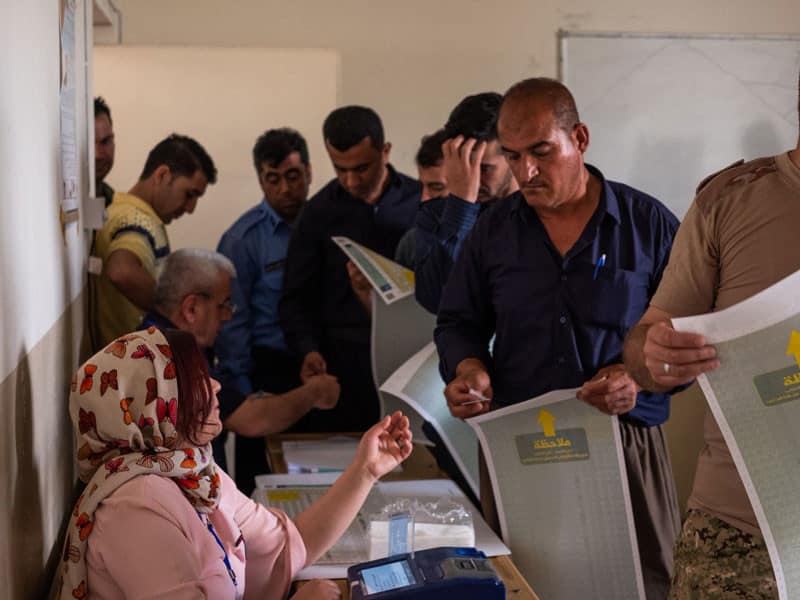

Elections become key instruments to structure political reintegration into existing institutions and processes. By doing so, armed groups and actors can come to adopt elections as an alternative to violence as a means of achieving political objectives. The transformation of an armed group into a political party epitomizes democratic norms under a rule of law while the restoration of civics endows citizens with agency within the state. In both cases, elections are the mechanism to achieve these ends, and in many aspects the linchpin to determine success in DDR efforts. Election laws may need to be amended to facilitate this transformation into a political party and such options as reserved seats for these nascent political parties may be one measure taken to assure that they are represented in government. Another measure is establishing women’s quotas for former female combatants to ensure they are included in the transformation process.

Educational and participatory tactical approaches should be considered in political reintegration programming. Illustratively, voter education, social media and other education activities can informformer fighters of all ranks and communities of the terms set forth in comprehensive peace agreements, the electoral and political processes, and what it means for former fighters.

Participatory programming can also integrate former women fighters and affiliates as candidates and voters, and even help others become active in a political party. For example, in choosing the leadership for the emergent political parties, these actors can conduct internal elections so that they can gain experiential learning on how to conduct an election.

Toward a Strategic Framework

The world is rife with insurgencies at a time when democracy is under attack by authoritarian regimes and populist movements. It is critical that in their transformation and restoration these actors correctly understand the principles of democracy and electoral governance. Otherwise, their values in this regard will be corrupted and the transformations will fail.

Given its institutional experience in both DDR and elections in non-permissive environments, Creative is uniquely positioned to address this issue through such an integrated approach to programming.

Dean Piedmont is Creative’s Senior Advisor for Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration and Security Sector Reform.