To achieve a unified, effective, and legitimate Libyan government, one of the U.S. Agency for International Development’s goals, development implementers should consider adopting a localized governance approach.

The Brookings Institution’s recent policy paper, “Empowered Decentralization: A City-Based Strategy for Rebuilding Libya,” makes the case for such an approach. Describing Libya’s political and economic landscape as “too atomized to be run by a strong central government,” this paper proposes that the United States de-prioritize national processes, such as elections, in favor of direct engagement with municipalities around politics, the economy and security.

The authors argue that this “city-first” paradigm would better respond to current realities on the ground and be a more effective method for helping Libyans build a more unified, peaceful and prosperous country.

Creative’s research into citizen perceptions of local governance systems supports Brookings’ analysis, and emphasizes the value of a city-based strategy. This research showed a wide range of variance between different cities in Libya, with each municipality having unique sets of challenges as well as opportunities.

Diverse challenges in Libyan cities

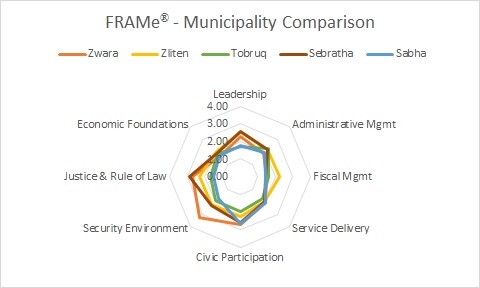

In December 2018, Creative conducted the Fragility Resilience Assessment Method® (FRAMe) in five cities in Libya: Sabha, Sebratha, Tobruq, Zliten, and Zwara.

FRAMe is a mapping tool that assesses the sources and dynamics of fragility at the community level along eight functional dimensions of governance (such as leadership and security environment) and seven factors (including inclusion, trust and legitimacy) that contribute to resilience. By gathering FRAMe data from different age cohorts and gender, Creative found that these five cities shared several commonalities—but that they have more differences than similarities.

Figure 1 illustrates shared perceptions regarding Administrative Management – that is, the regular functioning of municipal government – as well Service Delivery and Economic Foundations. However, perceptions diverged in leadership, financial management, rule of law, security and citizen participation.

Residents perceive Sebratha leadership to be inclusive, providing a base from which to address community challenges, but in Sabha leadership is perceived to be closed, making it difficult to bring about community cohesion.

Community-specific security concerns

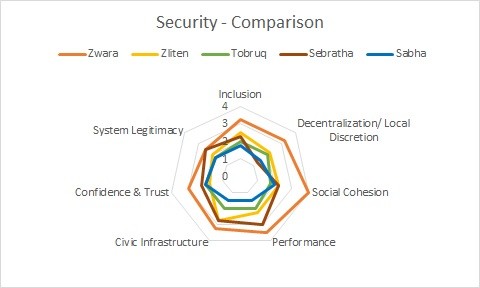

While the international narrative about Libya focuses on weak security institutions, widespread militia violence, and unchecked criminal and extremist organizations, FRAMe shows that the local-level experience with security varies widely from city to city.

For example, there was a wide range of responses regarding the prevalence of crimes and violence (under “Performance” in Figure 2). On the one side of the spectrum is Sabha, where illicit trafficking is a major source of income and state authority is particularly weak, and on the other is Zwara, where local authorities have been rigorously policing the community.

The Zwara scores suggest that the local authorities have been a more effective security provider than the police or militias working in the other four communities. Respondents in Zwara reported that the community is actively engaged in security management, security forces are fairly inclusive and mostly managed locally, and residents feel generally safe.

Zwara is weakest in the System Legitimacy factor – here, the state’s monopoly over security – but it is telling that even without strong government control citizens hold largely positive views of their security environment.

Inequities between identity groups

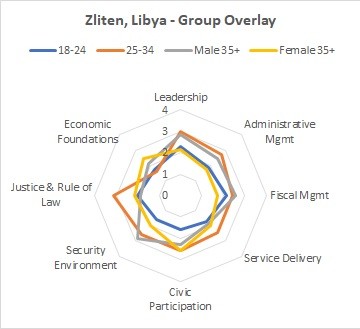

For Libya to progress on its path to self-reliance, understanding how youth—as eventual leaders of major institutions—perceive governance, and their ability to engage in building their respective communities, is critical. Data was collected from different age cohorts – 18-24 and 25-35, as well as adult men and women—to gain this understanding. In several of the community, FRAMe showed that different demographics held widely disparate views of their community.

The gap between youth and adults was most pronounced in Zliten (see Figure 3). In this case, youth ages 18 to 24 reported that municipal officials and security actors were untrustworthy and that they were excluded from engaging in civic life, discriminated against in the security and justice sectors, and shut out of the job market.

This group’s exclusion from Zliten’s governance system is contrasted by the experience of older youth, aged 25-34, who presented a very different picture, one where the government, courts, security forces and job market were generally inclusive and responsive to their needs.

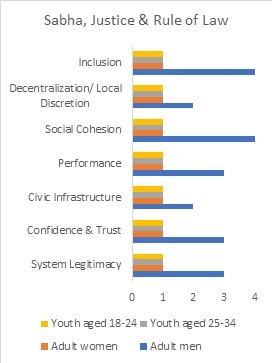

In Sabha, meanwhile, FRAMe indicated that the governance system is significantly biased in favor of adult men. Women and youth have much lower scores than men in every dimension of governance, but the disparity is particularly pronounced in Justice & Rule of Law (see Figure 4).

Men reported the justice system was fairly effective, legitimate and respected, as well as highly inclusive.

Women and youth, however, gave the lowest possible scores for every aspects of this dimension—from judicial accountability to the functionality of the prison system. Sabha’s gap in perceptions points to issues with access to justice and with discrimination, as well as a lack of awareness on the part of adult men in the city.

Creating constructive opportunities for the two youth cohorts will be important to building strong communities, today and in the future.

Using data to develop localized approaches

Creative’s FRAMe data illustrates the need for localized approaches. A single, national approach to security strengthening would be less effective than, for example, activities that build on the existing security structures in Zwara, while working with local authorities in Tobruq to establish new community security mechanisms.

The FRAMe data can also be used to tailor interventions to each municipality’s specific context. In Zliten, one priority would be to improve youth engagement in governance through targeted activities, such as establishing a Youth Council that would work with the municipal council on designing programs to support youth entrepreneurship. The Zliten Council could also reexamine its communications approaches, using social media to increase access to information and transparency around public finances.

Similarly, in Sabha the data suggests the need for governance actors to increase access for women and youth, address barriers to participation, and examine how to ensure services better meet all citizens’ expectations. With regard to Sabha’s justice sector, activities could begin with an analysis of the legal, structural, and cultural inequalities that are impeding women and youth’s access to justice and developing a program of reform based on those findings.

USAID has ambitious goals for Libya as a whole – a unified government, broad political inclusion, resilience to violent conflict, improved licit economic opportunities, and effective security and justice institutions. To meet these goals, USAID should develop evidence-based approaches that address the specific and unique conditions of Libyan communities on their own terms.

Maggie Proctor is a Project Manager in the Governance and Community Resilience Practice Area at Creative Associates International.