Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) has a longstanding “reading problem,” which has deepened with the impact of the pandemic on the region’s education system. Even after major pre-pandemic gains in the expansion of access to education and hundreds of millions of dollars of investments in literacy programs, the region is far behind on reading performance compared to global standards. Ultimately, more education has not translated into more quality education and improved learning outcomes for children in LAC.

Recent studies comparing reading scores from 2013 and 2019 (ERCE, UNESCO) show that for Grade 3 students, mean reading scores remained stable or decreased for most participating countries, with the exception of the Dominican Republic, Paraguay, Peru and Brazil. But even in countries experiencing some improvement in reading scores, most students are still below grade level standards in reading.

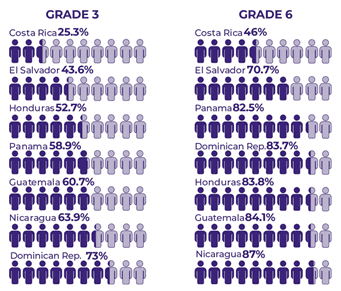

The graphic features ERCE results from 2019 and shows that throughout the region, the percentage of students performing below expectations in reading in both grades 3 and 6 ranged between 25 percent and 87 percent,

with the poorest scores coming from Central America and the Caribbean. Guatemala, Nicaragua and the Dominican Republic are consistently at the bottom of the pack in both grades.

So, what is happening? Why after six years and millions of dollars on education programming has there been so little progress in terms of children’s reading ability in the region? Why are we not seeing improvement, when we have learned so much about the science of reading in the last 10 years, and the research has pointed us to the core skills children need to master to be able to read fluently with understanding?

What makes these poor reading results even more astounding is the fact that Spanish is one of the easiest languages to master because of its relatively small alphabet and its transparent orthography, meaning each of the letters of the alphabet only have one sound. Compare this to the English language, which has a similar sized alphabet but where each of our letters can make multiple sounds, creating many more combinations and rules for children to learn. For example, in English, the letters ‘ough’ can be pronounced nine different ways (rough, plough, through, though, thought, thorough, cough, hiccough, lough) – whew! In Spanish, readers simply need to learn the 27 letters of the alphabet and the approximately 30 corresponding phonemes (or sounds). This means that it is easier for a child to learn the letters and their sounds and begin to combine those to form words (what we call decoding).

Gough & Tunmer’s Simple View of reading (1986) identifies two key skills that must be mastered to be able to read with comprehension and posits a simple equation which has been proven across languages and cultures: “Decoding x Language comprehension = Reading Comprehension.” In this equation, both skills are equally important and required for a child to be able to read with comprehension. First, they must be able to decode text. This means they must use their knowledge of the letters and the sounds they make to sound out words and to combine words into sentences. This is the act of decoding, and it should be a relatively quick process for children learning to decode in Spanish because of the small number of letters and sounds to be learned. But decoding does not equal understanding. For a child to actually understand what they are reading, they must be able to decode and understand the words they are decoding. This means that vocabulary must be explicitly taught, and children must learn academic vocabulary in addition to vocabulary they would use outside the school setting.

So, if we know how the science behind creating strong readers works, and that Spanish is a relatively simple language to read, why is there such a reading problem in LAC? There are many reasons why we have not managed to move the needle on reading rates in LAC in recent years, but these three require special attention and concerted action:

- Support teacher training and create awareness for the adoption of evidence-based teaching practices: We have not convinced ministries of education and teacher training institutions to adopt the science of reading. To be sure, this is something that even here in the United States has been a major controversy. Just google “Lucy Calkins and balanced literacy,” and you’ll uncover multiple articles about how some of the preeminent curriculum used in the U.S. did not align with the science of reading. And this is curriculum that was used at Columbia University’s Teachers College, which has trained hundreds of thousands of educators in the U.S. Children must be explicitly taught how to decode text, and phonics is the most effective way to do that, especially in a language like Spanish.

A 2020 regional study examining how teacher training institutions in Central America are training teachers to teach reading (Andrade-Calderón, Stone, & Vijil) found that many of the key reading skills are being overlooked. In addition, teachers are not being taught HOW to teach the key reading skills. The focus is much more on the content and the theory but vastly overlooks how to translate that into practice in an elementary school classroom. This means that when teachers enter the classroom, they often revert to doing the same things their own teachers did because that is what they have seen and experienced. There is a real need to update the region’s pre-service teacher training curricula to align with the evidence on how children learn to read and to provide concrete modeling and experiential practice for teachers before they enter the classroom.

- Align the basic education curricula: The basic education curricula in LAC does not often align with the evidence on what skills children need to learn to read. Curricula are not standardized across the region and even within each country, there is often great variation in what textbooks teachers use to teach reading. Many teachers in the region purchase their textbooks in the market, and there is not enough coaching or oversight to ensure any kind of uniformity across the system. Furthermore, the curricula that is used in the classroom often does not align with the curricula used in the teacher training colleges leading to a disconnect for teachers. Textbooks and teacher guides should be based on the science of reading and should also be included in teacher training colleges, so that teachers have the opportunity to interact with the curriculum they will be expected to teach prior to entering the classroom.

- Support inclusive education that addresses the needs of non-native Spanish speakers: The region has not seriously addressed the language issue that, according to UNICEF estimates, affects more than 40 million indigenous peoples who speak 420 different languages in LAC. The evidence is clear that children learn best in a language that they speak and understand. In addition, providing education in a child’s own language ensures that education is inclusive, as the children who do not speak the national language are often the most marginalized. Most countries in the region have a Spanish-only immersion policy, which means that students either sink or swim. For non-native Spanish speakers, such as Garifuna speakers in Honduras or Miskito speakers in Nicaragua, this means that young children enter school to learn math, reading and other subjects in a language that they do not speak. This is a huge disadvantage to those children who must learn a language and learn to read in that language at the same time, resulting in many of these children not learning to read at all or learning to read poorly, or simply dropping out of school completely. There is still more to be done to ensure that children are given the basic human right to learn in the language that they speak and understand.

Unfortunately, COVID-19 has only exacerbated the situation. We now face a period in which children have been out of school or have experienced greatly reduced time on task during the past one to two years. This is disastrous in a region where reading scores were already declining. Children in Latin America and the Caribbean experienced some of the longest COVID-19 school closures in the world.

“On average, students in the region lost, fully or partially, two thirds of all in-person school days since the start of the pandemic, with an estimated loss of 1.5 years of learning,” according to a World Bank study. This is an issue that must be addressed, and it must be addressed now.

As we celebrate World Literacy Day, we should collectively reflect on what that effort entails. Schools need to be fully reopened. Teachers need training on assessing student learning and providing remediation to help catch students up. Campaigns are needed to encourage parents to send children back to school and to reenroll and continue to support learning in and out of the classroom. And in the longer term we need to ensure that teacher training curricula and basic education curricula are aligned with the science of reading, and that children have access to a language they speak and understand. This is a massive effort, but one that is absolutely necessary to ensure that long-standing inequities in the region are not further deepened.

Rebecca Stone is the Technical Unit Director: Education at Creative Associates International

Claudia Salazar Suarez is the Senior Technical Manger: LAC Specialist at Creative Associates International