In the fall of 2012, nine teams set out across six provinces of Zambia, visiting 200 schools. Their task: collect data that would serve as a baseline against which to measure the success of a USAID-funded early grade reading program. The undertaking involved tracking the progress of a sample group of 4,600 students and teachers in 18 districts—and the teams arrived for their duties with just pen and paper.

They travelled to remote provinces; the project school closest to the capital city Lusaka was a seven hour drive away. When they reached these schools, the teams manually recorded the information on stacks of paper-based questionnaires. Then, with at least a week’s worth of these papers in tow, it was back to Lusaka where data entry clerks would manually enter the information from the completed questionnaires into spreadsheets.

It was a tedious system with some key drawbacks for Creative’s Read to Succeed project, which works in 18 districts of Zambia to address the poor learning and literacy among primary school students.

Chief among them was the realization after-the-fact that completed questionnaires from the baseline study were missing from some regions.

We had to send data assessors back to the field to re-collect information they had already gotten. As a result, a phase that was supposed to take no more than six months ended up taking a year.

When the process is on paper

Creative isn’t alone in our reliance on old methods for data collection in the field.

Development organizations accustomed to scrimping often worry about the costs of incorporating new technology—especially if it doesn’t work the first time.

They doubt that digital data collection and analysis will work in poor, rural environments where delicate equipment won’t hold up and reliable internet connections are a rare find. They may be unsure if data collectors can easily be trained on mobile data collection.

And as much as Creative would have liked to use mobile technology as soon as Read to Succeed started—indeed we had planned for it from the beginning—the timeline just didn’t allow for the long procurement procedures for getting digital tablets or testing them in the field.

Taking our data digital

For our midline survey two years later, we had enough time to develop an action plan.

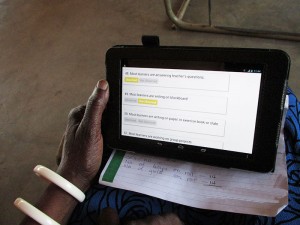

First we gathered all technical information about the use of tablets/notebooks, selected a survey-friendly tablet device to suit our needs (Nexus 7 tablets which are compatible with Tangerine, an open-source electronic data collection software developed by RTI International), and worked with technology experts from our home office to digitize survey questionnaires.

Next we trained our monitoring and evaluation staff on using Tangerine to enter and view data, and download reports. We also provided a 5-day training workshop to our 45 data collectors in Lusaka.

When our data assessors fanned out to the field sites, they collected data electronically from our sample of 4,000 students, 200 head teachers and 400 second and third grade teachers, randomly selected from 200 schools across 18 districts, including four where Read to Succeed was not active.

We found that even without an internet connection, our data collectors could log quantitative information and upload it later. Tablets could be charged using car chargers so that we weren’t reliant on having power in remote villages. None of this was being done just a year or two ago.

Immediate benefits

Using the tablets helped us achieve data collection and data entry concurrently—a significant time-saver compared to doing each of these steps sequentially as we had during the baseline phase.

A paper based system involved a lot of people- collectors, assessors, and clerks with dedicated computers. They take up conference rooms for months as stacks and stacks of paper occupy tables, cabinets and corners. Switching to digital data collection freed up salaries and space.

The system also has built-in anti-error mechanisms that reduce data entry errors. This ensured, for example, that a school in one district would not appear in another, which happened when we used the paper-based system.

With such a far-flung list of project schools, our monitoring and evaluation director had previously spent hours and hours driving around the country to monitor data collection—a recurrent and strenuous task during the baseline phase.

With the use of tablets, he was able to monitor the data as it came in live from screens in our main office in Lusaka. This not only reduced the stress that comes with travel but also contributed to better data quality since errors were corrected as soon as they were detected.

Of course our greatest benefit was eliminating the potential loss of hard copies.

Using tablets came with their own challenges such as the impossibility of editing entries once saved electronically. In addition, tablets as we used them cannot collect qualitative data. Furthermore, Tangerine software only allows data to be download in CSV Spreadsheet format. It’s not directly downloadable in other statistical programs likes SPSS, STATA or SAS.

But overall, thanks to our new approach we were able to collect higher quality data at a more reasonable cost and within a short period of time, plus reap the benefits of live monitoring. The process also had fewer errors than the paper-based approach and we did not need to physically store huge volume of documents in the office.

Even accounting for the upfront investment in software devices (we spent about $20,000 for equipment), internet connection and training-related costs, overall over the life of the project we saved time and money and—most importantly—came away with reliable information we can use to measure our project’s impact and make it better.

Creative’s Monitoring and Evaluation team in Zambia, led by Director Rhodwell Chitanda, contributed information for this piece. Photos by: Nephas Hindamu and Imasiku Wamuwi