Citizens in countries that are transitioning out of periods of prolonged conflict eagerly anticipate free and fair elections that will usher in leadership that can mend wounds, rebuild infrastructure and provide direction for a cohesive future.

In December 1995, after four years of warfare, the three major ethnic parties in Bosnia and Herzegovina convened in Dayton, Ohio, and agreed on a peace settlement. Called the Dayton Accords, they provided the framework and timeline for elections and to establish post-conflict national, entity and local governments.

The Dayton Accords called for elections to be conducted within six to nine months of the signing in December. In April 1996, I was appointed Director General of Elections and within five months, on Sept. 14 to be exact, the first cycle of voting was to be conducted.

Constructing the process

Our task was monumental—construct an in-country electoral process, establish in-person voting for refugees in countries bordering Bosnia and Herzegovina and establish procedures to allow absentee voting from more than 50 other countries.

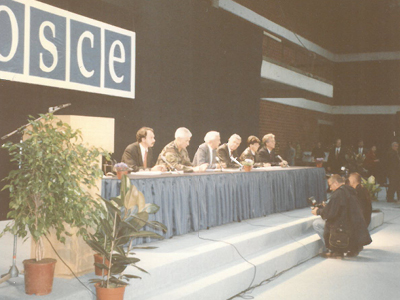

According to the Dayton Accords, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) was mandated to “supervise the conduct” of the election.

The September 1996 elections were complicated by a number of factors, including the conflict legacies, operating in a post-communist environment, translating voting messages into three languages (Bosnian, Serb and Croat) and safely moving candidates, voters, supervisors, journalists and observers in a country plagued with some 2 million land mines.

After four years of war, segments of the population were displaced. To determine citizenship and residency for the voter rolls, the 1991 census figures were used because they was considered to be the most accurate since it was conducted before the war.

In order to use the elections as a means to reverse the effects of ethnic cleansing, voters were given a variety of enfranchisement options: To cast their ballots from the current locations of residence; to vote absentee for the former residence; or to declare a “future intended residence” as the voting location.

The Provisional Election Commission was established and election rules and regulations were adopted. It administered the election in partnership with about 140 Local Election Commissions, which were responsible for recruiting poll workers and conducting activities at the polling stations. These Local Election Commissions assembled 300 registration committees, 144 counting center committees and 32,000 polling station committee members at 4,500 polling station sites.

In fulfilling its mandate, the OSCE deployed more than 2,000 supervisors to provide long-term and short-term election supervision at the local level. International election supervisors were afforded rights of intervention if they observed problems with the process.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s Implementation Force was used to provide security, as well as a variety of mission critical services including logistical support for transporting election materials and facilities for voter education training.

Criticism of the election

There were a number of criticisms of the election process.

For example, under the rules of the political party fund, parties led by indicted war criminals could not participate in the election.

One registered political party was found to be linked to the Party of Serbian Unity of Yugoslav Serb extremist Zeljko Raznatovic, known under his nom de guerre, “Arcan.” Arcan had been indicted by the International War Crimes Tribunal in The Hague for atrocities committed by his militia the Serb Volunteer Guard (also known as the Tigers) in 1995 in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

However, he had no direct leadership role in the Bosnian political party and there were no indicted war criminals serving in party offices or appearing on their candidate lists in violation of OSCE rules.

There were concerns that there were insufficient international supervisors to genuinely oversee the election process. Unfortunately, the election calendar did not allow sufficient time to train and deploy 4,500 supervisors (one per polling station), as well as the country’s inability to absorb such a large deployment. Instead the supervisors were assigned two or three stations to supervise on a rotating basis.

Finally, the International Crisis Group asserted that there was a 103.9 percent turnout of voters on Election Day.

The preliminary 1991 census, used for the voter registry, contained 3.5 million names of individuals, some of whom were no longer living. The enfranchisement options permitted people to cast their ballots in one of three locations. Therefore, the exact number of eligible voters could only be estimated since no separate registration exercise was conducted.

Mixed legacy to note

The outcomes of the election revealed a pattern of sectarian voting where the so-called “nationalist” parties of the Serbian Democratic Party, Party of Democratic Action and Croatian Democratic Union of Bosnia and Herzegovina won membership in the tri-partite presidency as well as pluralities in the national parliament and entity assemblies.

While the election was a political imperative to ensure the sustainability of the ceasefire, being conducted as close in time as it was to the conflict seem to harden sectarian lines rather than promote reconciliation.

In other words, people voted with and for the groups that protected them during the war.

As a result, while the international community embedded precedents of wide inclusivity, sought to reverse the effects of ethnic cleansing and assure that international standards are observed in the conduct of the process, identity politics prevailed.

Syria: Next major post-conflict election?

The next election intended for international supervision will be in Syria.

Though the war continues in Syria, the United Nations Security Council has adopted a resolution pertaining to U.N. supervision of the process.

When that happens, the lessons of 1996 will be relevant with respect to the conflict legacies, sectarian cleavages, and massive displacement of the electorate.

Jeff Fischer is a Senior Electoral Advisor at Creative Associates International.