Development companies hope multinationals become clients

By Jennifer BrooklandNovember 20, 2014

In a time of federal budget uncertainty, lingering sequestration anxiety and bursting competition for development dollars, international development companies should look to multinational corporations to expand their client roster.

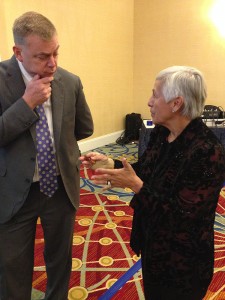

“There are companies out there bringing in billions and billions of dollars,” said Charito Kruvant, co-founder and CEO of Creative Associates International, who spoke at the Council of International Development Companies’ 2014 conference in Washington, D.C. “We have to grow, so we’re looking at our client base.”

Though Congress slashed the U.S. foreign assistance budget slightly less heartily than other appropriations, international development companies once reliant on U.S. government funding have increasingly eyed big business as a type of donor less prone to turnover, freezes and inefficiencies.

These development companies are also uniquely situated to provide real benefits to multinationals that recognize the humanitarian importance—and good business sense—of engaging with communities where they work, according to Stan Soloway, President and CEO of Professional Services Council, the national trade association of the government professional and technical services industry.

International development companies “are perfectly positioned to provide the needed interface between multinationals and emerging markets because they speak both ‘languages’ – development and free enterprise,” Soloway wrote in an introduction to a paper published by the Council and co-authored by Kruvant and colleague Bradford Strickland.

Better storytelling needed

Indeed, development companies like Creative are still figuring out how to use the syntax and colloquialisms of this language.

Indeed, development companies like Creative are still figuring out how to use the syntax and colloquialisms of this language.

“To appeal to the private sector, we need to know how to explain what we do and how we do it,” said Kruvant. “We need to tell our story of how wonderful we are at changing people’s lives.”

The way to do it isn’t always with nice pictures and brochures, she said, but hard numbers and statistics that business can use to improve their supply chains, incorporate technology and make their human resources more farsighted.

“We need to transfer our language in cross-cultural way to speak to those companies without giving up on our mission,” said Kruvant. “Understanding the private sector and understanding their precise needs lets us figure out how to be of service to them.”

Shared opportunity

Companies ranging from beverage distributers to clothing manufacturers can benefit from international development companies’ expertise in capacity building, negotiation and workforce development. But for that to happen, those multinationals need to know this community exists.

Many large companies do not automatically think to turn to international development firms when they work in emerging or fragile markets, just as development organizations are unsure of how to move beyond targeting a firm’s corporate social responsibility arm or foundation and partnering with the company itself.

Foundations only provided 10 percent of philanthropic funding in 2013, according to Susan Rae Ross, founder and CEO of consulting company SR International and author of Expanding the Pie: Fostering Nonprofit and Corporate Partnerships.

“The real money,” she said, “is in the business. If you want to think about doing HIV training for employees of Levi Strauss, that money comes out of the HR department.”

With 72,000 companies in medical technology company Medtronic’s supply chain, Managing Director of International Relations Dr. Trevor Gunn says the company’s fundamental problem is that it cannot find enough suppliers around the world—the perfect “in” for an international development company with expertise in livelihoods development, economic growth and capacity building: if Medtronic or a development organization thinks to partner.

“Do we really understand our future? We always think we do, and that’s why we need help,” Gunn said.

Corporations need help developing markets for smallholder farmers, for instance, or strengthening the health or education sectors, but are more likely today to turn to large nonprofits or boutique consultants, said Devex’s Raj Kumar, who moderated the panel.

The prospect of multinationals and development companies turning to each other could be a mutual opportunity, according to Denis O’Brien, Chairman of the global communications provider Digicel.

“There is a growing movement in corporate America and worldwide to make multinationals more responsible,” O’Brien said.

For big business, it is “your time to actually do something in countries where you generate income,” O’Brien said. “If you want to sleep at night and you’re making a lot of profits in a poor country like Haiti, you’ve got to do something that is super impactful.”

O’Brien recommended reinvesting profits back into community projects, and then running those projects as managers would the core business.

Kruvant and Strickland suggest companies are starting to do this: “Rather than channeling work through a Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) department, corporations seeking to affect positive change are using new products and services that are helping to build social impact into their everyday business practices,” they write.

The trouble with partners

Yet, as speakers at the CIDC conference pointed out, partnering with large companies is not a mindless solution for development organizations wishing to expand their pies.

They can be complicated to get off the ground, for starters.

“Most people underestimate the time it takes to do a partnership by at least 40 percent, especially in the development community when there’s a big gap between when you establish a partnership and when you get the funding,” said Ross. “In many ways doing these partnerships, you have to be a risk-taker.”

“I don’t have a bottom line that’s endless that will go on while we discuss partnership,” said Kruvant. “I need to be able to plan and deliver services for the next three years, not dance with CEOs who tell you how great you are. Think of us as vendors first, and then partners.”

But when that relationship is achieved, Ross pointed out that true partnership must extend beyond the bankroll.

Instead of hunting for a donor to support a cause, development firms must come to the table clearly able to articulate their assets and expertise, but also open-minded to the idea that big businesses want to have a hand in shaping the solutions, and not just funding them.